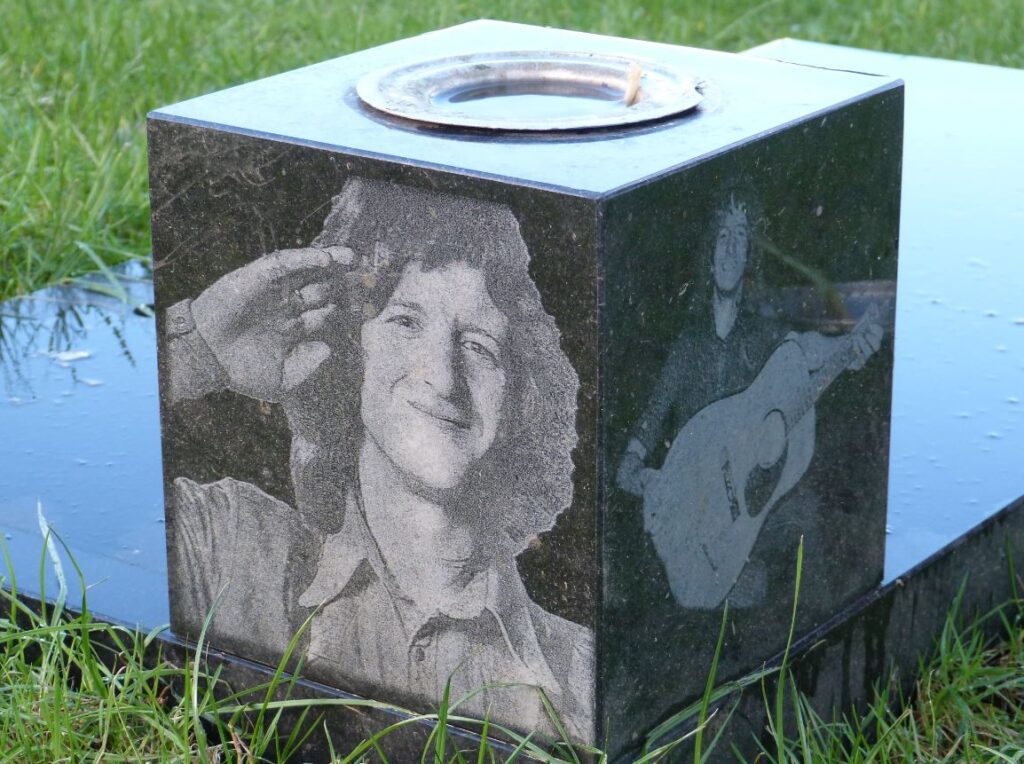

There is a memorial to Peter Ham. There were some concerns about errors by the stonemason on the memorial, sadly carelessly prepared, and the headstone was consequently removed. It is so important that it is correct and is a fitting tribute to a lost talent, for his loss has always been so keenly felt. The headstone is back now, a poignant reminder of a great musician that you can see in Morriston Cemetery, Swansea, where his ashes were scattered to the winds in 1975.

All those who loved his music also carry with them their own memorial. And what does it say? What else could it say?

Peter Ham.1947 – 1975. Free at last? Perhaps.

Of course, his memory lives on. He has been survived by his music. He still has an admiring audience. His piece Baby Blue, for example, was used at the end of the TV series Breaking Bad.

You would like to think that his group Badfinger are remembered for their superb music. But that is not always the case. Sadly they are more famous for their disintegration and their tragedy. Theirs is a cautionary tale, a story of how the naivety and idealism of youth was manipulated and abused by their cynical elders. Rock and roll doesn’t rule the world. It never did. Accountants do.

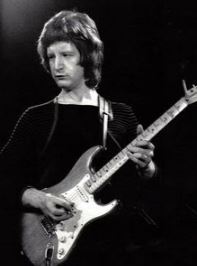

Peter William Ham was born on 27 April 1947 and he was brought up in the Townhill area of Swansea. Always musical, playing first the harmonica and then the guitar, he had dreams. His group was first called The Panthers and modeled themselves on The Shadows and then they became The Wild Ones. Peter Ham was enthusiastic and talented. His group developed a local reputation. They changed their name then to The Iveys, after Ivey Place in Swansea and also, perhaps, in the hope they could tap into the success of ‘The Hollies.’

They were playing the local dancehalls across South Wales and getting plenty of work. They were supporting bigger names and getting themselves known. They were marketable. Everyone said they had a future, but no one could have known what that future would hold.

After appearing at The Regal Ballroom in Ammanford, they were approached by Bill Collins, a manager who wanted to take them on. Suddenly they were professional, concentrating on their music. It seemed that their dreams might soon become real.

Collins moved the band to Golders Green in London. A new member joined, Tommy Evans, and their reputation grew. Then, at the end of 1967, The Iveys were offered a recording contract by The Beatles Apple label. Not only that, but Paul McCartney had heard a demo and wanted to produce them. They changed their name again, this time to Badfinger, based, apparently on an alternate title for the song With A Little Help From My Friends.

McCartney took them into the studio to record one of his own songs. Suddenly they had made it. Success. Come and Get It was a hit, across Europe and in America. That was important. That was where the money was.

It was also where the biggest sharks swam. In waters that were not safe enough for innocent Welsh boys, who just wanted to have a good time and play music.

They would not have recognised the great irony in their first hit record, this piece written by Paul McCartney, in which he expressed his bitterness about the financial confusion of the Apple Corporation – If you want it, here it is, come and get it but you better hurry ‘cos its going fast. Prophetic words. The kids who bought the record wouldn’t have known it, but the song was about money. How could they have realised? But if ever one song could come to encapsulate an entire career, it was this one.

Click on the link to see them (miming) on Top of the Pops

The key moment came quite unexpectedly at this moment of great excitement and great possibilities. They needed a financial manager for their forthcoming American tour that would cement their reputation. So in 1970, Badfinger enlisted a New York business manager named Stan Polley. He was highly recommended and Peter and the rest had little reason to doubt him, but it is said that he had well established connections with organized crime and a facility for complex and dubious financial arrangements. They would soon learn about this, to their considerable cost.

Their music was developing. Badfinger had moved on. They went for a harder edge, a more progressive sound, and they found themselves tuned perfectly into the spirit of the times.

Their album, No Dice, recorded in 1970 was very well received. Some reviewers called the band The New Beatles, although this would be an accolade it was impossible to live up to. But they were good and we liked them. Their music was infectious and well crafted. Peter Ham was writing his finest material and composed the band’s biggest selling single to date, No Matter What.

Click here to see them performing it

There was also a song on the album that unexpectedly achieved international recognition. The American singer Harry Nilsson heard No Dice and issued his version of the Ham/Evans composition, Without You. An international success. A standard. That one song should have guaranteed a prosperous future. An artistic and commercial achievement. Subsequently recorded by so many different people and in so many different ways. A great and enduring song. Sufficient you might think to retire upon. But I guess it’s not the way the story goes.

Follow this link to see them performing it live

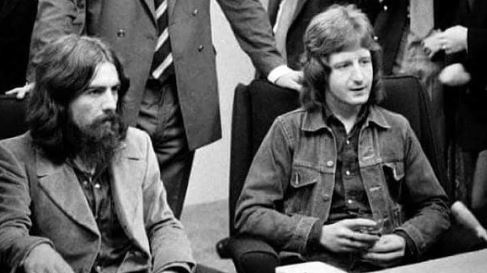

Musically they were achievers. Successful American tours, hit records. They performed at Madison Square Gardens in a concert to aid Refugees of Bangladesh. They shared the stage with George Harrison, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton. They appeared on albums by George Harrison and John Lennon.

Watch the video for Day after Day (my favourite) below.

Oh yes, Badfinger were stars in name, but in reality they remained financially destitute. The band had made a lot of money, but nobody knew where it was. The more famous they became, the more impoverished they appeared.

That’s the point isn’t it? If you want to make a living having a good time as a pop idol, someone has to do the grubby business of actually persuading people to buy your records. That isn’t quite so creative. Let someone else take responsibility for that. So it comes to pass that young pop musicians are ripped off.

Badfinger, like so many others, became a way in which accountants could make a serious amount of money.

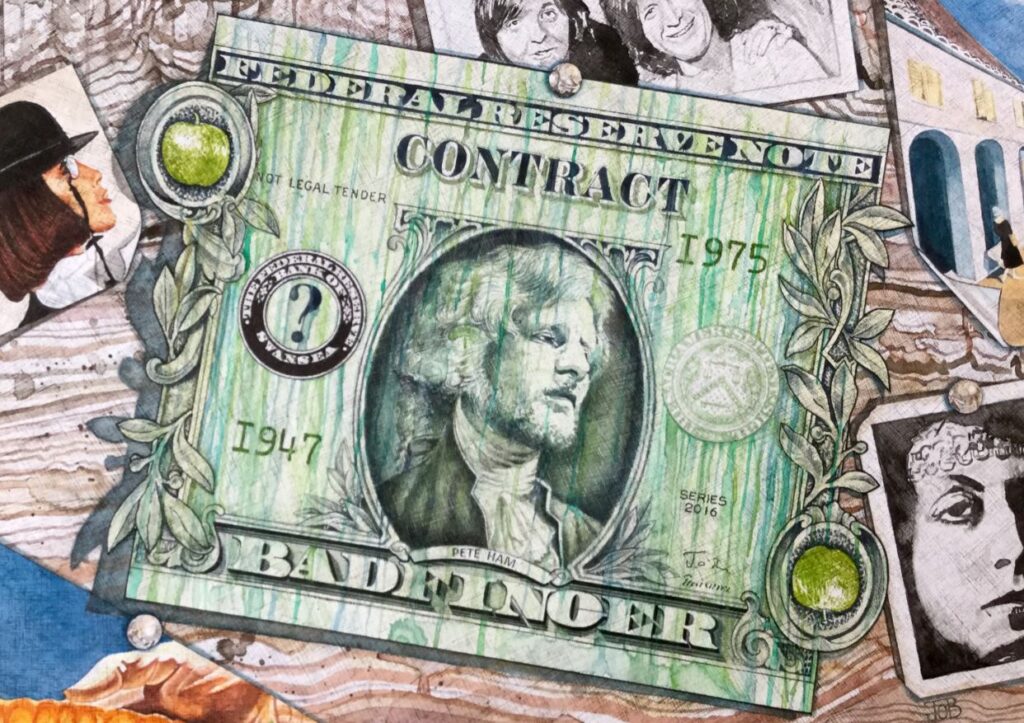

In 1972 their contract with Apple now completed, Polley moved Badfinger to Warner Brother Records for a reputed $3 million. The question would always be, what happened to it? It was a good deal for someone, but it put huge strains upon the group. They had finished their commitments to Apple with an album called Ass which had a sleeve on which they represented themselves as a donkey, following a carrot on a stick representing the promises of Polley.

But the new contract meant they had to produce another album for Warner Brothers immediately. It was a huge strain. The lyrics of their songs began to reflect their growing despair. We’re the pawns in someone else’s game, wrote Peter Ham. Tom Evans was equally forthright. In a song called Hey Mr. Manager, he said You’re messing up my life. And in Rock’n’Roll Contract, Tom wrote again about Stan Polley. You made me your slave. For the sleeve of this ultimately unreleased album, Tom wanted to portray the group being eaten alive by Stan Polley. They were making music desperately, churning out song,s and yet their advances were disappearing.

Others found out too. In 1975, a Warner Executive discovered that all the money from their joint account with Badfinger had disappeared and thus refused to market their work, threatening their group with breach of contract. $600,000 of advance money in a shared account wasn’t there. Nobody in the band knew where the money had gone. Their record company were keen to find out, too. It had been filtered from the account by the American management company. As a result, there were no Badfinger records available anywhere. Their business and musical affairs were now in a state of collapse. Peter Ham, composer of one of the most successful songs of his time, part of a group that sold an estimated 14 million records worldwide, couldn’t pay his phone bill. An innocent and exciting journey that had started in a dancehall in Ammanford had now reached its grim destination in the world of American contract law.

Suddenly they found themselves dealing with a weasel world for which nothing in their ordinary lives had ever prepared them. Contracts, lawyers, obligations. And of course big cheques that they never saw. When large amounts of money are moved about there are plenty waiting to shave a bit off. Or to bite out huge chunks.

They had been expecting a simple life. Peter Ham’s generation wanted to live in a world of bright splashy colours. They spoke of love, peace and happiness. There were others who lived off those dreams, inhabiting a grey world, like parasites.

This wonderful illustration by Jason O’Brien, which incorporates images from their album covers, captures so very well, the enduring tragedy of the band.

Peter Ham resigned from the group for a brief period in 1974 but it eventually all became too much to take. He had written three million-selling singles, had toured America six times, had songs covered by innumerable artists and had co-written a song generally considered a standard. Yet he was penniless. Everything seemed to be closing down. There was no escape. No hope.

On the evening of 23 April 1975, he walked into his garage studio, put a rope around a joist and hanged himself. He wasn’t quite 28 years old.

All he ever wanted to do was to play music. But it stopped being music some time before. It was product. Units to be shifted. Like microwave ovens. Refrigerators. Colour TVs. Quantity, not quality. And everyone wanted a piece of it. And in the end, a piece of him.

His suicide note, addressed to his girlfriend Anna and her son, blamed Stan Polley for his misfortunes:

‘Anne, I love you. Blair, I love you. I will not be allowed to love and trust everybody. This is better. Pete. P.S. Stan Polley is a soulless bastard. I will take him with me.’

Peter Ham was survived by Anne and daughter Petera, who was born one month after his death.

Badfinger disbanded after Ham’s death, but the lawsuits and bankruptcies didn’t cease on either side of the Atlantic. There was still money to be made out of Badfinger, but only by the lawyers. By 1977 Tom Evans was working as a plumber. Band members occasionally tried to revive the group and at one point there were two rival bands, both called Badfinger, but the brief glory days had gone, along with Peter.

But tragedy wouldn’t leave the band alone. By 1983 Tom Evans may have acquired a drinking problem, he may have developed throat cancer; he was in the process of losing his home and was being sued.

On 19 November 1983 Evans argued on the telephone, reportedly about the publishing royalty division of the song Without You. Following the argument, Evans hanged himself in the garden at his home.

I guess that’s just the way the story goes.

You always smile, but in your eyes your sorrow shows,

Yes it shows.

I can’t live if living is without you.

I can’t live, I can’t give anymore.

Peter Ham and Tom Evans had nothing left to give.

Here is another Youtube link.

Over the years I have researched many interesting Welsh Graves and when I have made presentations to various groups I have used this brief video to set the scene.

It is two Badfinger songs, used as the soundtrack to pictures of graves which are part of our common heritage. They fit quite well. See what you think.